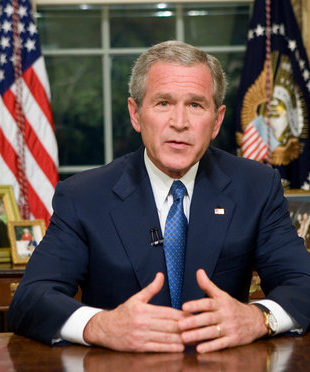

President Bush called for a $145 billion economic stimulus package on January 18, 2008. The plan centers on tax breaks for consumers and businesses to rejuvenate the lagging U.S. economy. The principles outlined by Bush opened a path to an agreement with congressional Democrats that could put as much as $800 in each taxpayer’s pocket by spring. The reaction in Congress revealed a divide between Democrats on the campaign trail, who assailed Bush’s proposal, and those in Washington, such as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (Calif.), who expressed optimism about reaching an agreement with the White House.

The $140b included in the stimulus plan is about 1% of GDP. That is a reasonable price to pay to attempt to stimulate the economy. It is not too much and not too little, but just enough.

Because the Bush administration is already running a deficit, the funding for his 2008 economic stimulus plan will likely have to come from borrowing, adding to the deficit.

“The ‘job’ of a recession is to clean the ‘fat’ out of the system, mop up excess, and pave the way for the next expansion. Until that process is complete, there isn’t much from which a legitimate expansion can arise. Recessions put weak companies out of business. In so doing, resources (skilled workers, capital) are freed up to be deployed more efficiently elsewhere. For example, Wall Street analysts who touted bankrupt Internet stocks are redeployed at local fast food restaurants to serve people in a capacity for which they are much better suited. Stronger businesses that have used the contraction to firm up their bottom lines and grow more efficient are able to take advantage of these resources during the ensuing expansion. The economy emerges from a recession leaner, more efficient and in good shape for the next wave of growth and progress.”

“While the logic seems sound, it doesn’t seem to match the data. If recessions were necessary to ‘clean the fat out of the system’, we’d expect there to be a lot of bankruptcies and firm closures during recessions and little during booms. The data, however, does not support this as you can see in the table on the bottom of the page [see article]. I have data for five different years, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2001 and 2002. The only year in the chart that overlaps with a recession is 1990, as the National Bureau for Economic Research indicates that the United States had a recession from July 1990 until March 1991. For the five years here, the GDP growth rate was positive in each year, from a high of 3.8% in 2000 to 0.3% in 2001. Notice how little firm closures differ between these five years. We do not see great differences in firm closures between periods of high growth and periods of low growth. While 1995 was the beginning of a period of exceptional growth, almost 500,000 firms closed shop. The year 2001 saw almost no growth in the economy, but we only had 14% more business closures than in 1995 and fewer businesses filed for bankruptcy in 2001 than 1995.”

Rebates put money into the hands of the lower and middle classes, who are more likely to spend their money on services or consumer goods. This is precisely the kind of economic kick that is needed in the economy. In addition, it is necessary for this money to be infused into the economy fast. Tax rebates to the lower and middle classes achieve this, since these groups are more likely to spend the money fast. Therefore, a tax rebate to the lower and middle classes is well targeted.

Numerous sources indicate that, in 2001, the rebates Bush provided of $300 to individuals and $600 to families had a significant impact on the economy. Various sources indicate that between 1/3 and 2/3 of the total rebate was spent in the first six months of the stimulus. Numerous sources indicate that the recession that year was relatively mild due to these steps, and could have been much worse otherwise. While the recession began in March it was over by November, even despite the September 11th attacks of that year.

Stimulus in forms such as tax rebates could bring relief for businesses such as restaurants facing recent minimum-wage increases, rising commodity prices and changes in customer spending.

Tax rebates do not give families ongoing wage strength. Therefore, the economic effects on the economy can only be short-lived.

The tax rebate plan is based on a failed premise: that taxpayers will immediately spend the rebate money they receive on consumer goods. But, with the current housing problems and huge debt, the money will probably not be spent on consumer goods, and rather to pay off loans. Furthermore, statistics show that Americans are gradually saving and conserving their money more often, which would be counter-productive to the plan.

If a case study is sought, this is the most recent example of the failure of the 2001 Bush tax rebates to help stimulate the economy. Numerous studies conclude that the 2001 tax rebate was a failure.

Technically, no American is gaining any money under this plan because taxes in future years will have to increase to cover for the $145 billion loss in the federal budget. “Injecting” money into the economy now means withdrawing money from the economy later. Therefore, the plan is a form of wealth distribution that passes much of the burden onto future generations that are not to blame for current economic failures.

Tax rebates are a cash give-away. There is nothing in them that increases incentives for workers to be more productive; whether they work hard or not, they will still be receiving the same tax rebate. Tax-cuts, on the other hand, incentivize increased productivity by creating a dynamic in which, if workers put in more hours and earn more money, they will be able to keep more of that money, instead of paying it away in taxes.

This is particularly true in Bush’s 2008 stimulus package, which aims to give a tax rebate to the lower and middle classes specifically because these classes are more likely to capriciously spend the money on consumer goods. Yet, given the debt-laden financial circumstances of the lower and middle classes, they should be using this money to pay down debts or simply should be saving the money. Therefore, the stimulus from a tax rebate depends directly on lower and middle-class consumers spending irresponsibly. Exploiting irresponsible behavior should not be the aim of economic stimulus packages.

It is often claimed that tax rebates for the middle and lower classes are good for the economy because they go toward spending rather to savings. But this assumes a false view of savings. If someone deposits money in their savings account at a bank, the bank is infused with more cash to lend out, which stimulates the economy. And, savers frequently save by investing, which stimulates capital flows, economic growth, and job creation.

Although tax rebates, increased unemployment benefits and other short-term payments may feel good and appear superficially attractive, they do very little to actually boost the economy and improve Americans’ well-being. Rather, cutting tax rates, not mailing tax rebates, is what stimulates prosperity. This is a critical distinction. The primary reason why tax rebates don’t work is that they merely redistribute existing wealth, as opposed to creating new economic growth or encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship. They do nothing to encourage risk-taking, investment or enlargement of the wealth pie, but instead re-slice the existing pie in a zero-sum manner.

Unemployment benefits are a critical backdrop for employed individuals. If their unemployment benefits are low, they may feel that it is important that they hedge against any possible risks of future unemployment by spending less and saving more. This is not stimulating for the economy. If unemployment benefits are increased, employed individuals will feel more confident in their decisions to spend money now, even if it does so happen that they are laid-off in the future; the extended unemployment benefits will still keep them secure. Therefore, UI provides a boost of confidence to workers in their choice to spend money and help stimulate the economy.

Few studies indicate that extending unemployment benefits helps stimulate the economy. Why this is the case is fairly straightforward. While it may be true that extended unemployment benefits makes some existing workers more confident that they can spend freely and still have a good safety net, those that are in the safety net of unemployment insurance feel too comfortable, and may not quickly search for new jobs. At the same time, employers use UI to hold together laid-off workers without paying them in times of low demand, waiting until things get better to finally re-hire workers. If UI is extended, employers will wait longer to re-hire laid-off workers they have on-hold with UI. Finally, UI has a fairly indirect link with consumption, attempting to stimulate confidence instead of providing a direct, sustainable infusion of cash to spend.

To access the second half of this Issue Report Login or Buy Issue Report

To access the second half of all Issue Reports Login or Subscribe Now